testiloquent

Testing-Essentials ▪ Think Like a Tester ▪ Test Strategy ▪ Test Tooling, Automation ▪ Test Analysis and -Design ▪ Performing Tests and Reporting ▪ Appendix

In This Article: Three Definitions of Quality ¦ Quality: For, By and About People ¦ More Quality, Less Quality.

The Meaning and Significance of Quality

Software testing is most commonly used as a quality assurance measure, so we’ll begin by delving into the what and why of quality.

Organisations have one or more products on offer.

Note: We’ll use “products” as an umbrella term to refer to the many forms an organisation’s offerings can take - goods, services, information etc..

Independent of the type or size of the organisation, having the ability to reliably and sustainably deliver quality to all important stakeholders will place it in a better position to continue to exist.

What Quality Is

Jerry Weinberg’s definition of quality - “value for some person” - may seem disconcertingly vague, but upon examination proves to be broadly fitting. 13

For many products or services, customer needs extend beyond the technological features of the good or service; customer needs also include matters of a psychological nature. – Juran 8

Quality isn’t an object or event, but an idea about the purpose of a product, and how the product ought to fulfill its purpose.

Each person’s notion of quality is the subjective, even idiosyncratic consequence of the set of relationships between a product, the person and the context. Exhibit A: The multi-Swatch wearer.

The watch of our choice offers us more than merely the ability to check the time. When people shop for a watch, the choice they make will likely be influenced by needs and expectations that have little or nothing to do with the purely utilitarian.

The individuals who in some way are affected by a product or who have some interest in it are the product’s stakeholders. In absence of stakeholders, the product-person-context set of relationships doesn’t form, which makes the question of the product’s quality irrelevant.

Quality Changes With Context

A person’s notion of quality is profoundly context-dependent. As people and the world they live in are always changing, the products or product characteristics that a person values are subject to change.

The changes can occur gradually over time, like our changing tastes in fashion through childhood, adolescence and adulthood. They can also happen abruptly, as was the case in 2020, when Covid restrictions were implemented by governments around the globe. In response to recommendations or mandates to wear a mask in public, people developed clear ideas about the attributes of a high-quality face mask.

- Most front line workers were likely satisfied if and when they finally had sufficient supplies of N95 masks.

-

For many people with hearing disorders, the wide-spread use of masks impacted understanding in interpersonal communication - masks hide lip movements and facial expressions, and the fabric can also reduce the volume and clarity of speech. Reusable transparent masks were costly and less convenient than disposable masks didn’t catch on. Disposable masks were more convenient, , as they were costly, and less convenient than disposable masks. Person for whom style is important: People whose aesthetic sensibilities were offended by medical masks were spoiled for choice. A myriad of DIY designs and ready-made products for sale could be found on sites like Pinterest and Etsy, where face mask couture was trending.

This is a pattern that Clay Christensen observed in his consulting work. He introduced the Jobs to Be Done theory in his book Competing Against Luck.

Quality is Immeasurable

When you can measure what you are speaking about, and express it in numbers, you know something about it, when you cannot express it in numbers, your knowledge is of a meager and unsatisfactory kind; it may be the beginning of knowledge, but you have scarcely, in your thoughts advanced to the stage of science. – Lord Kelvin

Lord Kelvin’s assertion may hold true for mathematics and things governed by the laws of physics, however the tools of hard science soon expose their limitations when applied to quality. Due to quality’s subjective, multifaceted, fleeting nature, there’s neither a universally applicable unit of quality nor a formula with which it can be directly and reliably measured.

Let’s look at definitions of quality from some thought leaders who have influenced testing theory. Philip Crosby and Joseph Juran worked on their philosophies of quality in the post-WWII era.

Conformance to Requirements - Philip Crosby

In his four Absolutes of Quality Management, Philip Crosby defined quality as conformance to requirements. The essential points of his definition are:

- It is necessary to define quality; otherwise, we cannot know enough about what we are doing to manage it.

- Somehow, someone must know what the requirements are and be able to translate those requirements into measurable product or service characteristics.

- With requirements stated in terms of numerical specifications, we can measure the characteristics of a product (diameter of a hole) or service (customer service response time) to see if it is of high quality. – Hoyer.

A shared understanding of what constitutes quality will \($enable\)$ those involved in developing a product to effectively align their efforts, so the first point is valid. The second and third points, however, are incompatible with the reality of software development projects:

- “someone must know what the requirements are”

When it comes to commercially used software products, there is most certainly not always someone who knows all the requirements.

Why not?- Customers may themselves be unaware of some of their requirements before they have had a chance to interact with a new product.

- Moreover, requirements are not static. They change over time as the context changes, so complete knowledge of them is a moving target. Clairvoyants are in notoriously short supply, even among business analysts and user experience designers.

-

“we can measure the characteristics of a product … to see if it is of high quality” Some important customer requirements simply can’t be translated into objectively measurable specifications.

For Crosby, when a quality goal is defined without measurements, “we cannot know enough about what we are doing to manage it”.

This presents a conundrum to managers who prescribe to Crosby’s definition of quality: if they don’t have a number for each requirement, they’re not… managing!once a model feels true, it is hard to shake, no matter how much countervailing evidence is presented.

Confronted with requirements that inconveniently refuse to conform to the measurement doctrine, managers may well apply surrogate metrics, convince themselves that these requirements have been magically transformed into something objectively measurable, and use their influence to ensure that others treat their chosen metrics as if they are measuring what matters.

The use of surrogate measures might relieve managers’ cognitive dissonance, but it solves no real business problems, wastes company resources and can backfire in unexpected ways.

Despite the issues with Crosby’s definition, it’s useful to be aware of it. It was widely accepted by IT decision makers for many decades, and many people still find it convincing.

Case in point: in a manner reminiscent of Crosby’s definition, the Wikipedia article on quality assurance describes quality as “agreed upon” customer expectations related to “performance, design, reliability, and maintainability”.

Expect to encounter it in your work life.

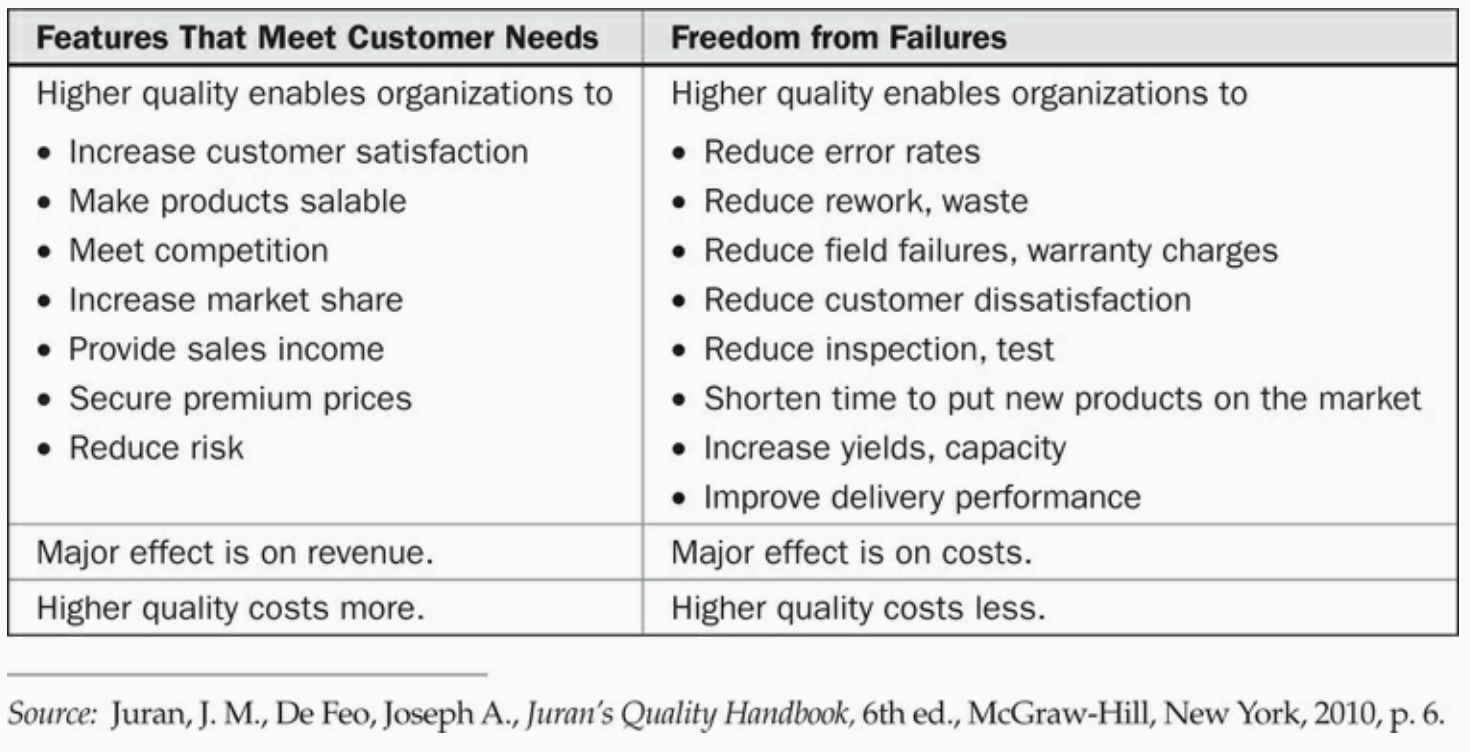

Fitness for Purpose - Joseph Juran

Juran’s definition of quality is “fitness for purpose”. That does require some clarification:

The purpose is always defined by the customer using the good or service.

Customers judge the quality of goods and services by how well they meet their needs. These needs drive the purchase of goods and services.

If an organization understands the needs of its many customers, it should be able to design goods and services that are fit for purpose.

No matter what the organization produces — a good or a service — it must be fit for its purpose. To be fit for purpose, every good, service, and interaction with customers must have the right features (characteristics of the good or service that satisfies customer needs) and be free of failure (no rework, no waste, no complaints).” – Juran

Customers Define Purpose Based on Their Needs

Juran is not counting on every company having a clairvoyant on staff who knows all customer requirements. He suggests that organisations can understand their customers’ needs and perhaps even anticipate the purpose which will later be given to their products.

Customers state their needs as they see them, and in their language. Suppliers are faced with understanding the real needs behind the stated needs and translating those needs into suppliers’ language.

With Juran’s management approach or with new ways of working such as outlined in the Agile Manifesto, organisations might be better equipped to develop this skill. Ultimately however, the future is unknowable - including the purpose future customers might attribute to a product.

Exhibit A: The multi-Swatch wearer.

What needs does a Rolex meet that a Swatch doesn’t, and vice versa? Could the creators of the first Swatch models have anticipated this usage of their product? Could they have found out about it from future customers beforehand - was this a requirement that future multi-Swatch wearers were aware of before Swatches were available to buy?

Once a product is in the hands of users, new purposes may emerge that the original stakeholders did not conceive of - as illustrated above in the picture of the person wearing multiple watches, or… anything you give your cat.

James Bach wrote about an experience he had with repurposing a tool - an interesting read.

Is there an algorithm for fitness?

Juran’s explanation of “fitness for purpose” hints at a formula by which fitness might be assessed: The elimination of rework, waste and complaints lowers costs and frees up resources for the organisation, putting it in a better position to serve its customers in the long term. For example, it might use available resources to deepen its understanding of customer needs by training or hiring user experience designers.

Value to Some Person - Gerald Weinberg

Throughout Jerry Weinberg’s book Perfect Software and Other Illusions About Testing, he illustrates how subjective value is, and how dependent on context.

His definition “Value to some person” emphasizes that all stakeholders, including customers, are people. Moreover, it highlights the fact that a diverse set of stakeholders - not only customers - have an interest in the quality of a product,and the degree to which their needs and expectations are fulfilled can impact business outcomes.

Consider the following stakeholders of a banking back office application for managing customers’ accounts:

- A developer on the team responsible for running and maintaining the application

- A manager who uses reports from the accounts system for a status report presentation

- A staff member who uses the system to create reports for several managers - each report having different content and layout

- An IT supporter who mans the phones at the bank’s help desk

- The bank’s paying customers who access their account information via an app that interfaces with this back office system

- A hacker looking for a way to stage a digital bank robbery

Each stakeholder above will have different needs and expectations with regard to the software, because each has a different “[Job to be Done][14]” shaping their notion of quality.

Quality is For and By and About People

Quality isn’t one size fits all, and it doesn’t stand still. It is relative, changeable and subjective.

Quality is not an object or an event. It’s not a thing. It’s a set of relationships between the product, some person(s), and the context.

There can be no absolute scale for quality. Quality is subjective and multidimensional. Perceptions of quality are relative to the person(s) who has (have) them.

Product elements (structure, functions, data, interfaces, platform, operations, and time, in the HTSM) are not quality criteria. A quality criterion is a category by which you might assess your satisfaction with the product or some element of it. – Michael Bolton

What counts as good (or bad) quality - and indeed what the purpose of a product or service is, as illustrated by the broken ice cream machines at McDonalds story - can differ considerably, depending on who you ask, when you ask, and the context factors relevant for that person at that time.

Without people, the term quality would have no meaning.

Peoples’ needs and expectations inform their decisions about the purpose of a product and its level of fitness for purpose.

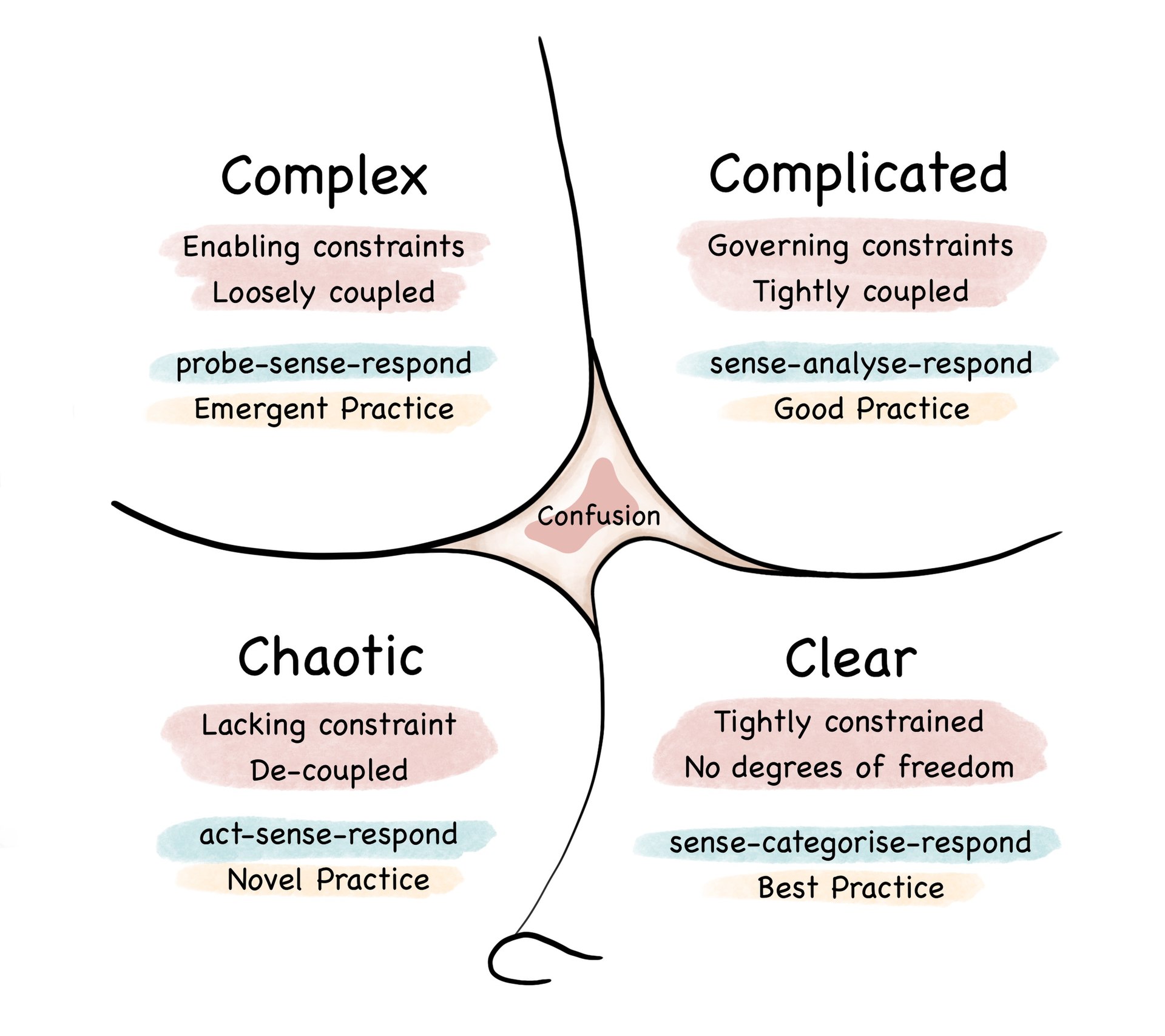

People systems are complex systems

Being a perception that changes with the context and differs from person to person, quality does not lend itself to “divide and conquer” analysis methods, and it evades attempts to succinct and precise definitions.

Complexity is not just a matter of there being many different factors and interactions to bear in mind, of uncertainty concerning some of them, of a multitude of combinations and permutations of possible decisions and events to allow for, evaluate and select.

It is not only a technical or computational matter, such as what engineers and operational researchers deal with.

Complexity is also generated by the very different constructions that can be placed on those factors, decisions and events. Complexity arises from the different perspectives within which they can be interpreted and the degree of emotional involvement people have in the situation. – Lane.

Getting to quality

We’ve concentrated on deeply clarifying the concept of quality as it emerges when a product or service is used. Customers satisfied with a product’s performance will continue to ‘hire’ it.

A company serving satisfied customers will be in a better position to achieve the ultimate business goal - to continue doing business. But given how “fuzzy” quality is, how do companies deal with the challenge of delivering good quality?

Good quality can’t reliably be produced by accident. This is where quality assurance - a process that takes different aspects of quality into account - comes into play.

We’ll continue to peel this onion in the upcoming chapters.

Previous: Testing Essentials. ▪ Next: SW Bugs.

22: [14]: https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/clay-christensen-the-theory-of-jobs-to-be-done